Efficiency, efficiency, efficiency: decoding yards per-play

- Israel Schuman

- Jan 8, 2023

- 4 min read

Updated: Jan 11, 2023

Efficiency is an economic term that describes the output produced with a given input. It is also the key to winning football games.

There are several ways to think about football in these terms. Games can be inputs, as can drives, series, or plays. Corresponding outputs can be points, first downs, or yards. Oftentimes, team stats are shown in terms of output "per input," like per-game, per-drive, and per-play. This, like any good experiment, isolates the input variable and makes it fixed, allowing the output, like points or yards, to show itself as a differentiator of team quality.

The takeaway from that paragraph is that "total" stats, like total yards or touchdowns, are useless. They don't measure efficiency, and thus are easily swayed by things that don't make teams good, like playing in a double overtime marathon. That will juice up player stat totals, but the tendency to play super long games is not something that we want influencing our perception of a team's quality. Or a player's quality for that matter, which leads me to my next point.

Efficiency is what matters for individual players too, as team stats are just a conglomerate of individual players' stats. If the players on a team produce a lot of points or yards or first downs per-play or per-drive, then that team will also do so, and will be good on offense. This gives us a basis for ranking teams and players: find a good stat for ranking teams, and then use the same stat to rank players. The stat we will be using for TFL Analytics is yards per play.

Team yards per-play explained

Why yards per play? Yards per play is a good way to see how much value (in terms of yards) that teams are generating. We could measure value in other ways, like points (first downs of course do not exist in TFL), but since some teams only play in three games and points come in bunches of 7, all it takes is one good or bad game to wildly throw off the numbers. We could also choose a different input stat, like drives or games. Unfortunately, team drive totals have not been kept by the league, and per-game stats are not specific enough, like in the afformentioned double overtime scenario where that game could have 30 plays per team while another has 5. Yards per play, then, includes ideal selections for input and output.

Player yards per-play

Finally, we need to come up with ways to measure yards-per play on the individual level. The way we do this is by observing the yards on a given play, and then assigning them to the players involved in the best way possible.

Take a play where the quarterback hikes the ball, stands in the pocket for 5 seconds, then runs past the rusher for 10 yards. That play was worth 10 yards for the offense, so that is our starting point. We then want to divvy those 10 yards up to the individuals who created them. The recievers did not get open enough for the QB to target them, so they get no yards on the play. The QB was then able to get past the rusher and create ten yards for his team, so we could credit him with ten yards per rush. But doing so would complicate our quarterback's influence on his team's yards per play by putting this play into a seperate category from the quarterback's passing plays, even though they all count the same for his team. Instead, we should count his ten yards as yards per drop-back, which are the number of yards gained every time the ball starts in his hands on a play.

Let's imagine the next play starts again with the quarterback, but this time he is able to find a reciever downfield for 20 yards. Crediting this play is trickier, because these yards were created from an interaction between two players. Let's go over what the receiver did first. He ran his route, creating enough separation for the QB to target him, and then he caught the ball for a 20 yard gain.

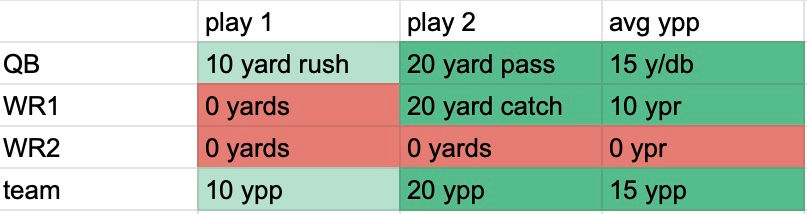

We could give him 20 yards per catch, but that would seperate this play from all the other ones where he didn't have a catch, and thus produced zero yards for his team. Instead, we could count it as 20 yards per target, but this again excludes plays where he didn't get open enough to be targeted, and did not benefit his team. We will instead opt for 20 yards per route, as that is the most direct way to measure a receiver's impact on his team's yards-per play. That play would also count as 20 yards per drop-back for the QB. Here is a way to visualize how the stats would be kept on the plays described:

For a team that has the same QB for every pass play and only runs with its QB, the QB's yards per drop-back would also be the team's yards-per play. For a receiver who only played receiver, his yards-per route would just be his total yardage divided by the number of QB drop-backs.

As you can probably already imagine, individual player yards per-play relies on a lot of context to be valuable, and given that context over a multi-year sample, it becomes a really powerful tool in ranking players on offense. If a quarterback consistently posts high yards per-dropback with recieving corps that change every year, he is a good quarterback. The inverse is also true. In the same vein, if a receiver is always putting up monster numbers, especially to the extent that he makes different quarterbacks also look excellent statistically, he is a good reciever.

As the TFL expands to include many different player combinations over an increasing number of seasons, we at TFL Analytics are seeing more clearly than ever who the studs and scrubs really are.

Comments